Ukraine offensive defies Russia’s annexation plan

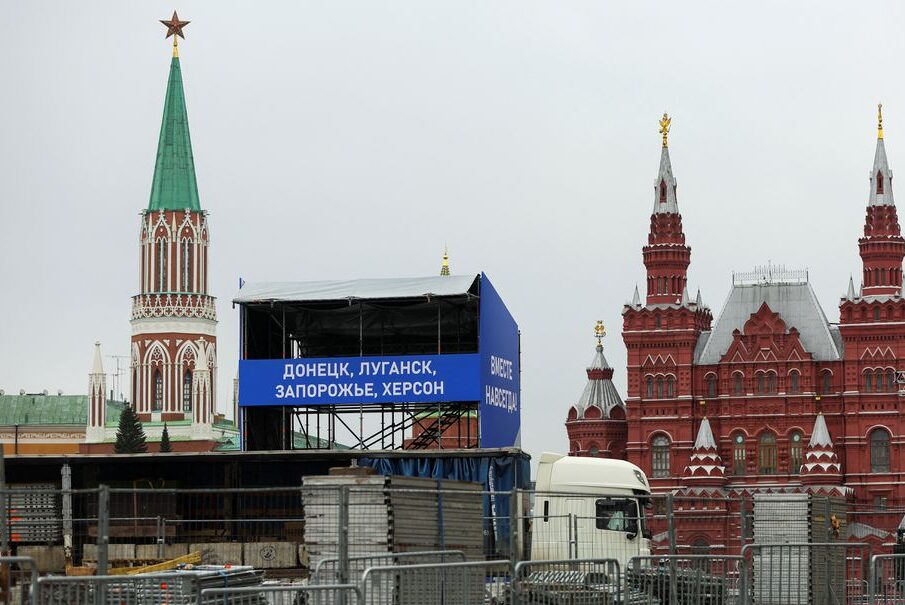

A view shows banners and constructions ahead of an expected event, dedicated to the results of referendums on the joining of four Ukrainian self-proclaimed regions to Russia, near the Kremlin Wall and the State Historical Museum in Red Square in central Moscow, Russia September 28, 2022. Banners read: "Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson. Together forever!" REUTERS/Evgenia Novozhenina

A view shows banners and constructions ahead of an expected event, dedicated to the results of referendums on the joining of four Ukrainian self-proclaimed regions to Russia, near the Kremlin Wall and the State Historical Museum in Red Square in central Moscow, Russia September 28, 2022. Banners read: "Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson. Together forever!" REUTERS/Evgenia NovozheninaAs Russia prepares to annex four Ukrainian regions, Kyiv’s forces are finishing the job of driving Moscow’s retreating troops out of a fifth and threatening their foe’s supply lines.

On Friday, the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia will be incorporated into Russia in a Kremlin ceremony that will be rejected by most international capitals.

But the Kharkiv region, an early target of Moscow’s February 24 invasion and home to Ukraine’s largely Russian-speaking second city, will not feature in the event, after a stunning counteroffensive.

On Thursday, Ukrainian tanks and armoured personnel carriers were manoeuvring freely through the industrial town of Kupiansk in the east of the Kharkiv region, once a key Russian supply hub.

Kupiansk hosts a severely-damaged bridge across the Oskil river, a natural barrier that the retreating Russians had attempted to hold, and a rail line once used to supply the occupation forces.

“This is a major railway hub that connect to the Luhansk region and then onto the Russian railway system,” said Kupiansk’s new Ukrainian military administrator Andriy Kanashevych.

“So obviously, in terms of logistics and in terms of supply, it was important for them to control it,” he said.

Russian forces did try to hold Kupiansk, despite the collapse of their front outside Kharkiv city and their catastrophic retreat across northeastern Ukraine, leaving wrecked tanks in their wake.

‘Car for his mother’

On September 19 the west bank of the Oskil was in Ukrainian hands, but an artillery duel was under way and the built-up areas on the east bank were still fiercely disputed.

On Thursday, for the first time, the town was secure enough for the fire brigade and civilian volunteers to pass food packages hand-to-hand over the shattered ruins of the bridge.

A single corpse in Russian fatigues lay by the eastern end of the span under a cloud of flies, as medics carried sick and wounded civilians back towards the west on stretchers.

“That’s a Lada Kalina for his mother,” one of the Ukrainian volunteers joked about the corpse, referring to reports Russia is compensating the families of slain servicemen with new cars.

The road deck of the bridge has collapsed into the river and only the pedestrian footpath along the side is passable for troops and civilian refugees crossing between the banks.

Two dozen men are needed to pass the 2,000 British-supplied ration boxes across the gap to be loaded into a truck for distribution to the most recently liberated areas on the east bank.

Despite the damage to the town centre bridge, Ukrainian forces have found an alternative way to move heavy vehicles, including tanks and Western supplied APCs to the east side.

The tanks have fanned out, backed by infantry and — despite the occasional incoming shell — have secured a large urban area, including places that had been occupied for seven months.

The battle knocked out water and electricity and many civilians have left, leaving Kupiansk with around 10 to 15 percent of its pre-war population of 27,000, according to Kanashevych’s estimate.

As late as Tuesday there were still Russian forces in the industrial district of Kupiansk-Vuzlovyi, five kilometres (three miles) south of the bridge — and civilians are only to starting to leave.

“It was really tough, really tough. We were terrified… with no water, no electricity, no gas, no mobile connection,” said Ludmyla Nagaytseva, 52, as families cooked in the open.

“There was no way. Only today we managed to catch a weak signal.”

On Thursday, a Ukrainian armoured personnel carrier and infantry platoon stood guard in front of the district cultural centre as local residents boarded buses to take them to the bridge.

‘Like prison’

One old man staggered out of the building shouting and gripping the left side of his chest. As his knees buckled and he collapsed to the ground, the troops’ medic rushed to administer first aid.

The speed with which Kupiansk fell in the first days of the February invasion fed suspicions that the area’s Russian-speaking population harbours divided loyalties between Kyiv and Moscow.

Most local people encountered by AFP seemed relieved to be liberated by Ukraine, and some were overjoyed. One man, 30-year-old business owner Maksim Korolevsky, said the town had been betrayed.

“On February 24, a lot of people, about 200 or so local guys, came to the enlistment centre to fight for Ukraine,” he told AFP, blaming the town’s former pro-Russian mayor, Gennadiy Matsegora.

“But on February 25, Russian APCs with Russian flags and Russian soldiers were in front of the place. What could we do? We couldn’t do anything,” he said, complaining of harassment and searches.

“Every pro-Ukrainian opinion was punished by Russia,” he said. “Seven months under occupation, it was just like being in prison.”

The Russian flags and soldiers have gone from Kupiansk now, but the invasion’s notorious “Z” symbol is still visible — painted onto wrecked military vehicles and bullet-riddled civilian vans.

Beside two of the cars lie bloated corpses in military boots.

© 2022 AFP